Introduction.

The Antiviral Development Landscape – 4th Edition

based on data from July 12, 2024 to December 18, 2024

In support of the G7’s recommended 100 Days Mission and the International Pandemic Preparedness Secretariat (IPPS), which seeks the “development of at least two ‘Phase 2 ready’ therapeutic candidates against the identified viral pathogen families of greatest pandemic potential,”1 the INTREPID Alliance committed in July 2023 to conduct a global landscape assessment of antiviral compound R&D. The landscape analysis intends to aid in the identification of clinical (e.g., Phase 2/3 ready) and preclinical antivirals aligned with the 100 Days Mission and highlight gaps in the pipeline.

INTREPID released the first three editions of the landscape analysis in January 2024, April 2024, and October 2024. These updates were based on non-confidential information and provided the initial summary of the clinical and preclinical phase antiviral compounds across 13 viral families of pandemic potential.2,3,4 Clinical compounds were classified as noted in the updated definitions below.4 Preclinical compounds were classified as previously described.4

With today’s release of the Antiviral Clinical and Preclinical Development Landscape – 4th Edition we begin our scheduled reports with emphases on the changes in compound classification since the previous edition. The fourth edition is based on evaluation of non-confidential information as of December 18, 2024. Going forward, these INTREPID landscape reports will be updated semi-annually or more frequently if substantive changes in the landscape occur.

Section One.

Antiviral Landscape Changes Since the 3rd Edition published on October 9, 2024

When comparing the 4th Edition analyses described below with the previous edition, we noted the addition or forward progression of some compound/indications while others were classified as archived or discontinued. All INTREPID landscape reports are based on publicly available, non-confidential information.

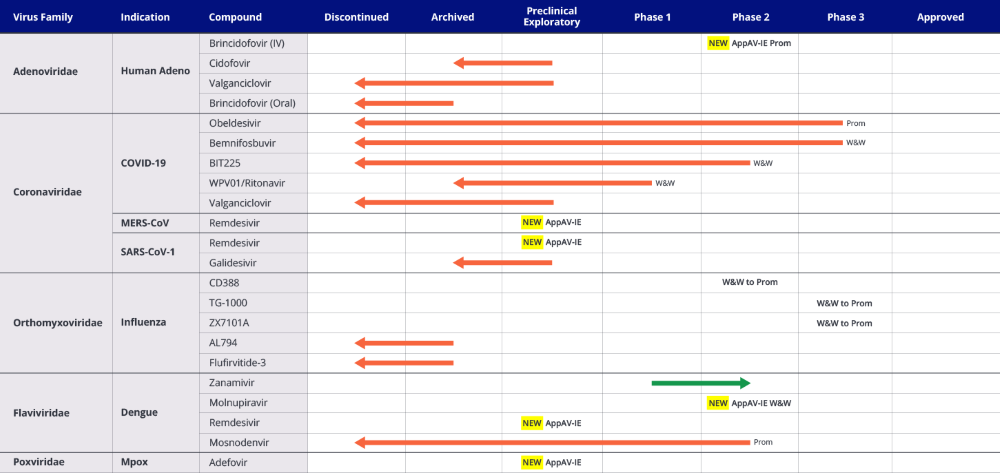

For Clinical phase compound/indications (Table 1), substantive changes from the 3rd to the 4th Edition analyses of the antiviral landscape include:

- 12 compounds discontinued/archived

- 6 new clinical compounds added

- 1 compound progressed

Table 1. INTREPID Alliance Clinical Antiviral Landscape: New Additions and Changes in Status from 3rd to 4th Edition Analyses*

*As of December 18, 2024. AppAV: approved antiviral; InvAV: investigational antiviral; IE: indication expansion; Preclin Explor: preclinical exploratory.

For Preclinical compounds (Table 2), those with only preclinical data, substantive changes from the 3rd to the 4th Edition analyses of the antiviral landscapes include:

- 2 Hit

- 12 Early Lead

- 2 Late Lead

- 5 Potential Candidate

Table 2. INTREPID Alliance Preclinical Antiviral Landscape: New Additions and Changes in Status from 3rd to 4th Edition Analyses*

*As of December 18, 2024.

The higher number of Non-COVID-19 preclinical compound additions under Newly Archived or Discontinued were primarily the result of deeper literature searches that captured compounds deemed useful to include in the landscape archives.

Section Two.

Classification of Clinical Phase Compounds4,5

Our analysis now reveals that there are 67 distinct direct-acting antiviral compounds, ‘regulatory approved’ or ‘investigational,’ that together account for a total of 103 viral indications across 9 of 13 priority viral families.3 Of these 67 compounds, 22 are approved for a specific viral indication by a stringent authority (S.A.) or other national regulatory authorities (O.N.A.). Some approved drugs are being evaluated clinically for additional viral indications (i.e., Indication Expansion) and these are also highlighted in the clinical landscape. In addition, 3 other antiviral compounds (e.g., adefovir, brincidofovir (I.V.), and cidofovir) are approved for viral indications outside of the 13 viral families of interest but are under evaluation as potential indication expansions within the 13 viral families. Finally, some approved antivirals (N=4; adefovir, cidofovir, favipiravir, and remdesivir) are being evaluated in preclinical exploratory studies towards other viral indications and these are now included in the landscape under the classification ‘Preclinical Exploratory’ with their respective new exploratory indications.

The INTREPID Alliance has identified a total of 42 novel compounds that are 'Investigational’ across various phases of clinical development for the 13 viral families of interest. These investigational clinical compounds account for 47 viral indications and are classified as described below in the subsection Compounds in Clinical Development.

In terms of pandemic preparedness aligned with the intent of the 100 Days Mission, clinical compounds in the following categories could be considered as Phase 2/3 ready:*

- Promising (compounds that we assess to be “100 Days Mission Ready”) (n=12),

- Watch & Wait (compounds which readiness for 100 Days Mission cannot be fully assessed at this time) (n=27)

- Investigational Antiviral-Indication Expansion (compounds that we assess to be “100 Days Mission Ready” based on clinical trials for a primary viral disease indication, but the clinical efficacy studies for the indication expansion are ongoing) (n=1)

- Investigational Antiviral-Indication Expansion Preclinical Exploratory (compounds that we assess to be “100 Days Mission Ready” based on clinical trials for a primary viral disease indication but have only undergone preclinical exploratory evaluation for the indication expansion) (n=7)

As clinical development is a dynamic process these compounds will be followed closely, and the landscape classifications will be updated and adjusted every 6 months, or more frequently if substantive changes are noted.

Developers and Sponsors of Clinical Phase Compounds

Our analysis, as of December 2024, found that the biopharmaceutical industry (both large and small companies), represents 89.3% of the global antiviral clinical developers for the Approved/Investigational Antiviral-Indication Expansion, Promising, and Watch & Wait categories. Academia represents 7.3%, government groups represent 2.4%, and contract research organizations represent less than 1%. For these compound/indications, the developers/sponsors are located in 13 countries, with 50.7% in the United States, 19.1% in China, 11% in Japan, 5.1% in Switzerland, 3.3% in Russia, and the remaining 14.1%, each at 2% or less each, spread across Australia, Belgium, Canada, Hong Kong, Pakistan, Taiwan, United Kingdom, and Vietnam. The Americas WHO-Regions6 has the highest percentage of developers/sponsors (52%); this being driven primarily by the U.S. and some in Canada (1.3%). A total of 35.8% are based in the Western Pacific region, followed by 11.1% in the Eastern Mediterranean and 1.1% in Southeast-Asia regions. Finally, the majority (~78%) of developers/sponsors are based in high-income countries, led by the U.S., followed by China (upper-middle income, ~19%), and the remainder (~2%) being in Pakistan and Vietnam (lower-middle income).

View Now